The Himalayas of India: Ladakh and Dharamsala,

Summer 2008

Ladakh - The Amazing Hemis Festival, Moravian Mashup, Women's Alliance,

Sankar

Page 7 of 16

I

walked up to the upper roof, providing a clear vantage point of the

courtyard below. A man at the top of the stairs stopped me. "You need a ticket," he said.

I showed him my 250Rs ticket. I

walked up to the upper roof, providing a clear vantage point of the

courtyard below. A man at the top of the stairs stopped me. "You need a ticket," he said.

I showed him my 250Rs ticket.

"You should have a 150Rs ticket for here," he muttered. "Yes, and I paid 250Rs, so I should also get a nice chair," I insisted. He hesitated, but my infallible logic had undoubtedly won him over, and he waved me past. This was the first time I had gotten in to a designated area, away from the pushing throngs. Then I ran into a travel agent I had met from Leh who greeted me warmly. With a belly full of noodles and no one leaning on my shoulders, I felt reenergized, and began shooting photos unimpeded.

|

The

Hemis Festival could be quite funny. Here, a ghoulish demon with

grinning skeleton head quickly darted in and out of the crowd, surprising

people and causing much laughter among the audience. The

Hemis Festival could be quite funny. Here, a ghoulish demon with

grinning skeleton head quickly darted in and out of the crowd, surprising

people and causing much laughter among the audience. |

It

began raining heavily again. Since we were on the top roof with no

awning, many of us ran for cover. Many in the audience everywhere

started leaving. I made my way past the throngs to the courtyard

again, having far better views and less people surrounding me than before.

I hid my camera inside my waterproof jacket, quickly pulling it out only to

take photos. It

began raining heavily again. Since we were on the top roof with no

awning, many of us ran for cover. Many in the audience everywhere

started leaving. I made my way past the throngs to the courtyard

again, having far better views and less people surrounding me than before.

I hid my camera inside my waterproof jacket, quickly pulling it out only to

take photos. |

These

performers danced by large puddles in the courtyard, impishly stamping their

feet to spray water on the already-soaked audience, who laughed and smiled. These

performers danced by large puddles in the courtyard, impishly stamping their

feet to spray water on the already-soaked audience, who laughed and smiled. |

One

of the Western tourists in the audience, standing in front of the

Padmasambhava Temple at Hemis, had an impressive selection of bold Indo-Western

attire. I know this because I saw him eating breakfast at Gesmo's in

Leh several times. One

of the Western tourists in the audience, standing in front of the

Padmasambhava Temple at Hemis, had an impressive selection of bold Indo-Western

attire. I know this because I saw him eating breakfast at Gesmo's in

Leh several times. |

The

festival ended for the day. I talked to a monk for a while, and then

left, joining the teeming masses streaming downhill. The

festival ended for the day. I talked to a monk for a while, and then

left, joining the teeming masses streaming downhill.

Some of the beads sold at the concession stands lining the path down from the Hemis Monastery. |

On

the way down, I met some nuns for Sankya Monastery, who were raising money

to build a nunnery in Choglamsar. I wished them well, giving them a

donation. On

the way down, I met some nuns for Sankya Monastery, who were raising money

to build a nunnery in Choglamsar. I wished them well, giving them a

donation.Unfortunately, getting back to Leh wasn't that simple. It continued raining. I stopped and talked to a few of the monks, and went inside the main temple to hang out. When I came out, there were still streams of people walking downhill. The problem is that there were no buses to meet any of these streams of people. The only buses we saw were already full and pulling away. After about an hour of waiting for buses, about half of us, numbering in the hundreds, started walking downhill towards Karu, along the main highway. We were all soaking wet and shivering while walking downhill. I don't know how long that took, but it was several kilometers away, and it seemed to take a really long time. |

Crossing

across a dirt lot towards the dirt road after crossing the Indus River, we

saw a

small bus stop along the main road, and immediately, a crowd of

probably 15-20 Ladakhis in front of me started running towards it

frantically. Despite lugging my SLR camera and a large pack, I sprinted and somehow managed to beat all

but two of them onto the bus, which probably only held 25 people. We were

all grateful to be out of the rain and the wind. We crossed back over

the river, went back up towards Hemis and then headed back to Leh on a much

rougher road. Crossing

across a dirt lot towards the dirt road after crossing the Indus River, we

saw a

small bus stop along the main road, and immediately, a crowd of

probably 15-20 Ladakhis in front of me started running towards it

frantically. Despite lugging my SLR camera and a large pack, I sprinted and somehow managed to beat all

but two of them onto the bus, which probably only held 25 people. We were

all grateful to be out of the rain and the wind. We crossed back over

the river, went back up towards Hemis and then headed back to Leh on a much

rougher road.And then.....BOOOM! What was that? The sound of a very large tire suddenly going flat. This took half an hour to fix. Trying to make lemonade out of lemons, I opened the window and stuck my camera out, photographing the changing of the tire, causing some laughter among several people. We eventually returned to Leh safely. The first thing I did was take a really long hot shower. The second thing I did was take my soaking wet muddy pants to the "lundry" man. The third thing was a delicious dinner at the Tibet Kitchen. |

13

July Sunday - After the rain and pushing and shoving and debacle of getting

back from the Hemis Festival, I decided not to attend the second day and

sleep in. However, after a delicious breakfast of fruit and yogurt, I

decided to witness another spiritual spectacle, that of a Sunday church

service in Leh. 13

July Sunday - After the rain and pushing and shoving and debacle of getting

back from the Hemis Festival, I decided not to attend the second day and

sleep in. However, after a delicious breakfast of fruit and yogurt, I

decided to witness another spiritual spectacle, that of a Sunday church

service in Leh.The Moravian Church was established here in the 1800s, and the church is still here today. I had previously met the pastor of the church a couple of weeks ago, inquiring about a diary telling about a Russian explorer who had allegedly discovered scrolls telling of Jesus coming to the Himalayas. "The diary disappeared 40 years ago, stolen, along with a great many other things," the pastor said. "I've been here 27 years, and haven't seen it." Numerous others had already inquired about it, and so I had already anticipated this answer. He invited me to take photos and attend a church service. And so I did. The insanely loud church bell rang, announcing that service was about to begin. Here, the church service was a Moravian mash-up delivered in Hindi, Ladakhi, Nepali, and English. Many of the people in attendance were from Nepal, singing and praying alongside Ladakhis, Indians, and the odd tourist. In the front was, curiously, a drum set and a Marshall combo amp, although neither was ever used. People removed their shoes and filtered in, sitting on the floor. The Moravians had translated Christian songs in Ladakhi, and sang them accompanied with an acoustic guitar, the voice and guitar both being fed through an ever-humming P.A. system. A young Indian man named Sadhu Nityananda (see photo above) told an often humorous story about how he became a Christian, constantly gesticulating wildly and peppering his lively speech with the occasional "Praise the Lord!" or "Thank you, Jesus!" |

Then,

a nervous man got up and read from a Hindu Bible, wobbling

to and fro. Then,

a nervous man got up and read from a Hindu Bible, wobbling

to and fro.Then, more interpreting of the Bible in Nepali. The pastor got back up and sang another song sung in Ladakhi while Father Michael and Sadhu Nityananda moved through the crowd, blessing each person. One woman, who had been crying occasionally, upon being blessed, suddenly crumpled to the floor, breathing wildly. When Sadhu Nityananda got to me, he said in a low voice, "May the spirit of the Father enter within you." while vibrating my shoulder vigorously with one hand and touching my head with the other. Whether good or bad, I remained standing. Others raised their hands, muttered things quickly, or interjected "Hallelujah!" as the song continued. Eventually, the service ended, and outside, women passed out crunchy Indian snacks and fried peanuts and Coca-Cola and smiled as we put on our shoes, ending a Himalayan church service. I love India. |

14

July - This was my last full day in Ladakh. I had talked to Dorjai.

He suggested that I walk up to the

Women's Alliance. "They show a film there in the afternoon that

you'll find very interesting," he said. And I did, wishing that I had

seen the film on the first day in Ladakh, not the last. The film

illustrated how modern conveniences come at a cost. Ladakhi farmers in

the past had been self-reliant, irrigating the melted snow for their use.

But now, they and their children were being taught in school that their

long-standing traditions, which had worked for thousands of years, were

"ignorant" and "backwards". Drinking water was brought in large

trucks. Some farmers had become reliant on this water. Where

before, they may not have had money but had everything they needed from the

land, they were now dependent on government water. 14

July - This was my last full day in Ladakh. I had talked to Dorjai.

He suggested that I walk up to the

Women's Alliance. "They show a film there in the afternoon that

you'll find very interesting," he said. And I did, wishing that I had

seen the film on the first day in Ladakh, not the last. The film

illustrated how modern conveniences come at a cost. Ladakhi farmers in

the past had been self-reliant, irrigating the melted snow for their use.

But now, they and their children were being taught in school that their

long-standing traditions, which had worked for thousands of years, were

"ignorant" and "backwards". Drinking water was brought in large

trucks. Some farmers had become reliant on this water. Where

before, they may not have had money but had everything they needed from the

land, they were now dependent on government water. |

At

Women's Alliance, we saw a film called "Ancient Futures". This

film began by telling about Ladakhi life, its interdependency on family,

neighbors and community, and how Ladakhis had been self-sufficient for

generations. Ladakhis had surpluses of food, knew how to do everything

themselves, with their children right alongside. At

Women's Alliance, we saw a film called "Ancient Futures". This

film began by telling about Ladakhi life, its interdependency on family,

neighbors and community, and how Ladakhis had been self-sufficient for

generations. Ladakhis had surpluses of food, knew how to do everything

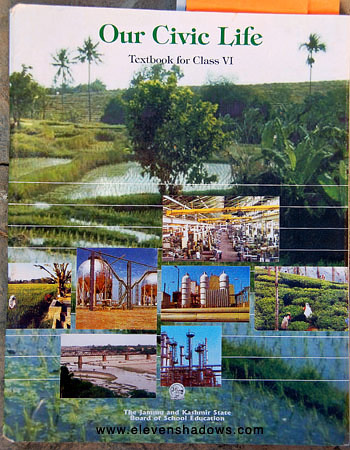

themselves, with their children right alongside.The second half of the video was a sobering look at what modernization has suddenly brought Ladakh. 130,000 Ladakhis in a place the size of England besieged by tourists numbering 50,000, the introduction of purchased goods, and the advent of TV and movies and MP3s since Ladakh had opened for tourism in 1974 had caused a sudden dependence on government subsidies, kerosene for fuel, cheaper mass-produced wheat brought up from the Punjab and a loss of identity. The modern world had suddenly been thrust upon them. And what was largely eroding this is what Spanzin had mentioned in Tangtse - the education system. Ladakhis were not being taught their own culture or language. Instead, they were being taught Hindi, forced to study the poetry of Wordsworth. ~~~~ The cover of "Our Civic Life", a children's textbook that was used in Ladakhi elementary schools. |

But

even worse, the film said, they were being taught that their way of life was

"backward", and away from their parents, they were not taught any of their

traditions, creating a giant gulf between them and their parents.

Essentially, the film stated, generations of children were being taught how

to be unemployed. There were few government and teaching jobs

available. The students were being taught skills they would not be

able to use, and knew virtually nothing about their own culture, or for that

matter, how to do anything in their "backward village". The women in

the village, with their children away at school, took on more responsibility

on the farm, becoming overworked. But

even worse, the film said, they were being taught that their way of life was

"backward", and away from their parents, they were not taught any of their

traditions, creating a giant gulf between them and their parents.

Essentially, the film stated, generations of children were being taught how

to be unemployed. There were few government and teaching jobs

available. The students were being taught skills they would not be

able to use, and knew virtually nothing about their own culture, or for that

matter, how to do anything in their "backward village". The women in

the village, with their children away at school, took on more responsibility

on the farm, becoming overworked.And the film also pointed out that while traditionally, Ladakh has always had surpluses of supplies and food, on government censuses, they would be considered well below poverty line. So with well-intentioned government subsidies, they had created a situation where Ladakhis needed money, and therefore, jobs. And as this wasn't happening, suddenly, real poverty and slums were occurring in Leh and elsewhere in Ladakh. ~~~~ This textbook, "Our Civic Life", issued by the Jammu and Kashmir state, has phrases such as: "The following are some of the causes for the backwardness of our villages". |

This

same textbook goes on to say, "The majority of our rural population is poor

and ignorant." This

same textbook goes on to say, "The majority of our rural population is poor

and ignorant."I was appalled by the textbooks, and the "Ancient Futures" film on Ladakh left an impression on me. The difficulty here, I realized, was the suddenness of modernity. But once exposed to modernity, it's difficult to deny that to anyone. Ladakhis have as much right to solar panels for electricity, clean drinking water, DVD players, tractors, Cheetos, and Bollywood action movies as anyone else. But striking a balance - how would anyone in Ladakh achieve that? Because the tiny region is besieged with tourists numbering well over a third of its own population each summer, Ladakh has become a bizarre science experiment in what happens when modernity collides with tradition within a very short time. |

As

if this film wasn't enough, one of the speakers handed out flyers telling us

to avoid Coca Cola and Pepsi products. In 2006, the government of the

state of Kerala in India banned the production and sale of both Coca-Cola

and Pepsi after the Centre for Science and Environment, a NGO, found high

levels of pesticide residue in the popular soft drinks. I found it

funny that Coca Cola continued selling products with "100% trust" emblazoned

on their labels. As

if this film wasn't enough, one of the speakers handed out flyers telling us

to avoid Coca Cola and Pepsi products. In 2006, the government of the

state of Kerala in India banned the production and sale of both Coca-Cola

and Pepsi after the Centre for Science and Environment, a NGO, found high

levels of pesticide residue in the popular soft drinks. I found it

funny that Coca Cola continued selling products with "100% trust" emblazoned

on their labels. |

After

that sobering dose of reality from the film and textbook at the

Women's Alliance, I decided to walk over to Sankar Gompa, set among

Upper Changspa's peaceful upper farmland. After

that sobering dose of reality from the film and textbook at the

Women's Alliance, I decided to walk over to Sankar Gompa, set among

Upper Changspa's peaceful upper farmland. |

Trumpets

ready for playing at the Sankar Gompa in Upper Changspa near Leh. Trumpets

ready for playing at the Sankar Gompa in Upper Changspa near Leh.This was my last full day in Ladakh. Tomorrow, I would travel to Dharamsala by way of Delhi. |

The Himalayas of India: Ladakh and Dharamsala, Summer 2008

Page 7 of 16

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

Eleven Shadows Travel Page

Contact photographer/musician Ken Lee